Peripheral neuropathy with Sjögren’s may ease with immunosuppressants

Condition accompanies Sjögren’s in up to about half of patients

People with peripheral neuropathy co-occurring with primary Sjögren’s syndrome may see their symptoms ease or even disappear with immunosuppressive therapy, a study found.

Researchers observed that Sjögren’s patients who tested positive for certain self-reactive antibodies or had too high levels of proteins called globulins in the blood were at a higher risk of peripheral neuropathy.

The study, “Analysis of clinical features and risk factors of peripheral neuropathy in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome,” was published in the European Journal of Medical Research.

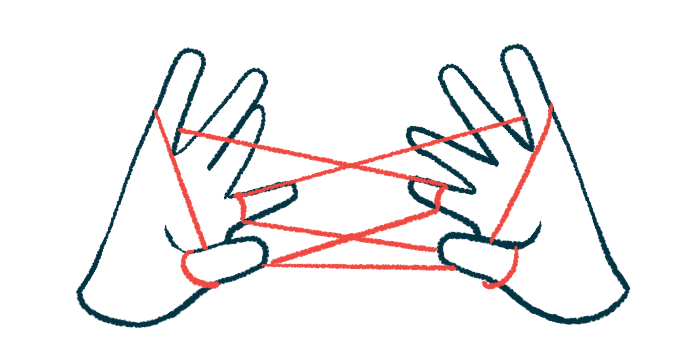

Sjögren’s is an autoimmune disease that causes certain glands to not produce enough moisture. This can result in dryness in many parts of the body, such as the mouth, eyes, and skin. Peripheral neuropathy accompanies Sjögren’s in up to about half of cases.

The condition develops when nerves in the body’s extremities, such as the hands and feet, become damaged. Its symptoms depend on which nerves are affected and not all people with co-occurring Sjögren’s and peripheral neuropathy are alike. This can make it hard for doctors to agree on the best treatment.

The researchers looked at the medical records of 60 people with Sjögren’s who were admitted to a hospital in China between January 2014 to June 2020. All had been diagnosed with the primary form of the disease, which means they had no other underlying autoimmune disease.

Of them, 15 (25%) also had peripheral neuropathy. Their mean age was similar to those with Sjögren’s who didn’t have peripheral neuropathy (55.5 vs. 56.2), but their disease had been ongoing for a median of three years longer (seven vs. four years).

They also appeared to have Raynaud’s phenomenon more often, a condition where the flow of blood to the fingers and toes slows or stops, causing them to become painful and numb (60% vs. 28.9%).

Anti-SSB antibodies also occurred more often (80% vs. 44.4%) in people with both Sjögren’s and peripheral neuropathy, as did rheumatoid factor (66.7% vs. 40%). Both are linked to developing Sjögren’s.

Hyperglobulinemia — abnormally high levels of globulin proteins in the blood — was more than twice as common in people with Sjögren’s who also had peripheral neuropathy than those who didn’t (73.3% vs. 33.3%).

People with Sjögren’s who tested positive for anti-SSB antibodies or rheumatoid factor had an up to 9.66-times greater risk of having peripheral neuropathy. That risk increased by 6.21 times for those with hyperglobulinemia.

Of the 15 people with co-occurring Sjögren’s and peripheral neuropathy, 14 (93.3%) were treated with immunosuppressants. These included glucocorticoids in all 14, cyclophosphamide in eight, hydroxychloroquine in seven, mycophenolate mofetil in five, and methotrexate in two. Azathioprine, rituximab, gamma globulin, and belimumab were each used by one person.

Over a median of two years, the mean modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score, a measure of motor impairment where a higher score means more disability, went from 2.21 to 1.21.

Most (71.4%) people saw their symptoms of peripheral neuropathy either partially or fully ease, “indicating that immunosuppressive therapy was effective,” the researchers wrote.