Myeloid Cells Increase Inflammation, Worsen Sjögren’s Symptoms and Prognosis, Study Suggests

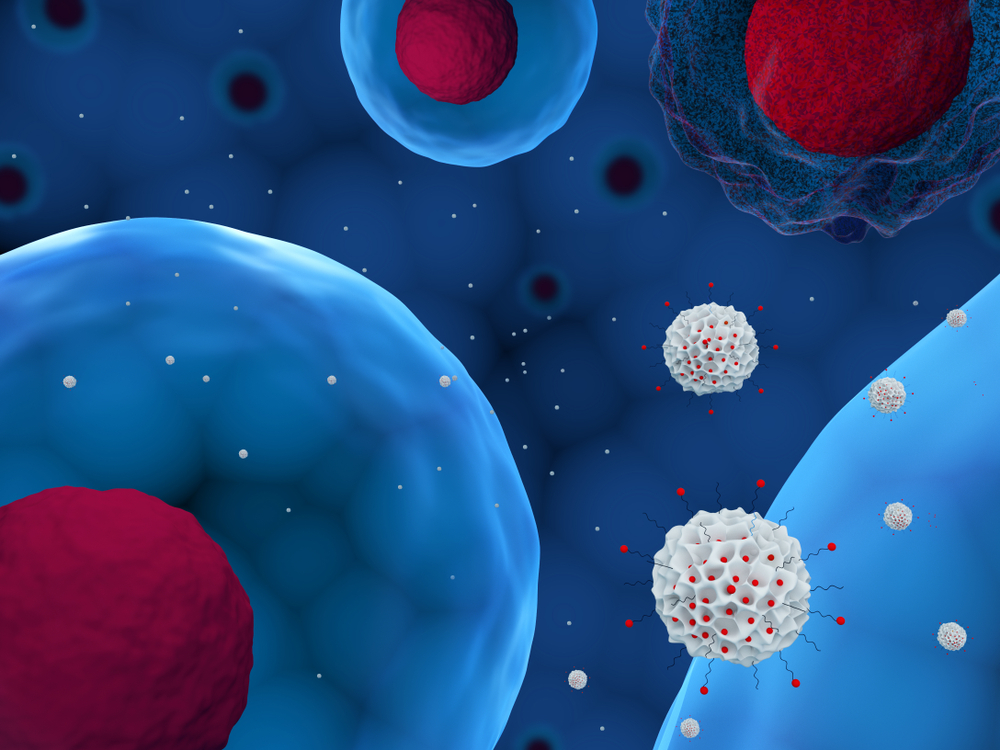

A type of immunosuppressive cells called myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), high levels of which were found in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome, seem to worsen the symptoms and prognosis of the disease, a study reports.

While the results seem counterintuitive, researchers found that MDSCs act on other regulatory immune cells, reducing their number and activity, which increases tissue inflammation.

The study, “Myeloid-derived suppressor cells exacerbate Sjögren’s syndrome by inhibiting Th2 immune responses,” was published in Molecular Immunology.

MDSCs are a type of cell derived from the bone marrow that control the activity of immune cells. In normal conditions, MDSCs strongly inhibit the activity of T-cells — immune cells that detect and destroy substances or other cells that the immune system sees as threats — but during inflammation, infection, or even cancer, their numbers increase dramatically.

Recent studies suggested that MDSCs are also involved in the development of several types of autoimmune diseases due to their pro-inflammatory action, including systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. However, their role in Sjögren’s syndrome was not clear.

In this study, a team of researchers in China set out to explore the role of MDSCs in human subjects diagnosed with Sjögren’s syndrome and in a mouse model of autoimmune type 1 diabetes mellitus (non-obese diabetic, or NOD, mice).

They collected blood samples from 40 Sjögren’s patients and 40 age-matched individuals used as controls to determine the frequency of MDSCs.

In addition, to study their function in a disease context, the scientists transferred MDSCs that were either untreated or treated with an anti-Gr1 antibody — an antibody directed against a protein from the surface of MDSCs called granulocyte-differentiation antigen-1 (Gr-1) that is widely used to eliminate these cells — to NOD mice.

The percentage of MDSCs was significantly higher in blood samples from Sjögren’s syndrome patients than in healthy controls. In addition, researchers found that the number of MDSCs increased with disease progression and inflammation in NOD mice, confirming that the number and immunosuppressive abilities of MDSCs were directly correlated with Sjögren’s severity.

As expected, when scientists transferred untreated MDSCs to NOD mice, the symptoms of the disease significantly worsened. Conversely, the deletion of MDSCs following treatment with anti-Gr1 in NOD animals alleviated these symptoms.

They also found that MDSCs significantly reduced the levels of T helper type 2 (Th2) cells — a subtype of T-cells that regulate the function of other types of immune cells, such as B-cells and killer T-cells — in patients and animals with Sjögren’s.

“To our knowledge, this is the first report linking MDSCs and Th2 cells to the [development] of SS [Sjögren’s syndrome]. However, the specific mechanisms on how MDSCs affect Th2 cell responses and how Th2 cell responses improve SS disease need to be further explored,” the investigators said.

These findings suggest that MDSCs worsen the symptoms and prognosis of Sjögren’s syndrome by reducing the levels and activity of Th2 cells.

“We revealed that MDSCs expansion positively correlated with inflammation and involved in Th2 cell response during the progression of Sjögren’s syndrome. … These results confirmed the significance of MDSCs and Th2 cells in SS and indicated that targeting to MDSCs and Th2 cells may lead to a novel therapeutic approach for SS,” the researchers concluded.