Immune Cells Found in Sjogren’s Patients Could Serve as Biomarkers of Other Autoimmune Diseases, Study Suggests

High levels of certain immune regulatory cells – called T follicular regulatory (Tfr) cells – in the blood are associated with Sjogren’s syndrome, researchers found. Scientists believe these cells could be used as biomarkers of certain autoimmune diseases.

The study, “Human blood Tfr cells are indicators of ongoing humoral activity not fully licensed with suppressive function,” was published in the journal Science Immunology.

It was conducted by researchers at Instituto de Medicina Molecular João Lobo Antunes in Portugal.

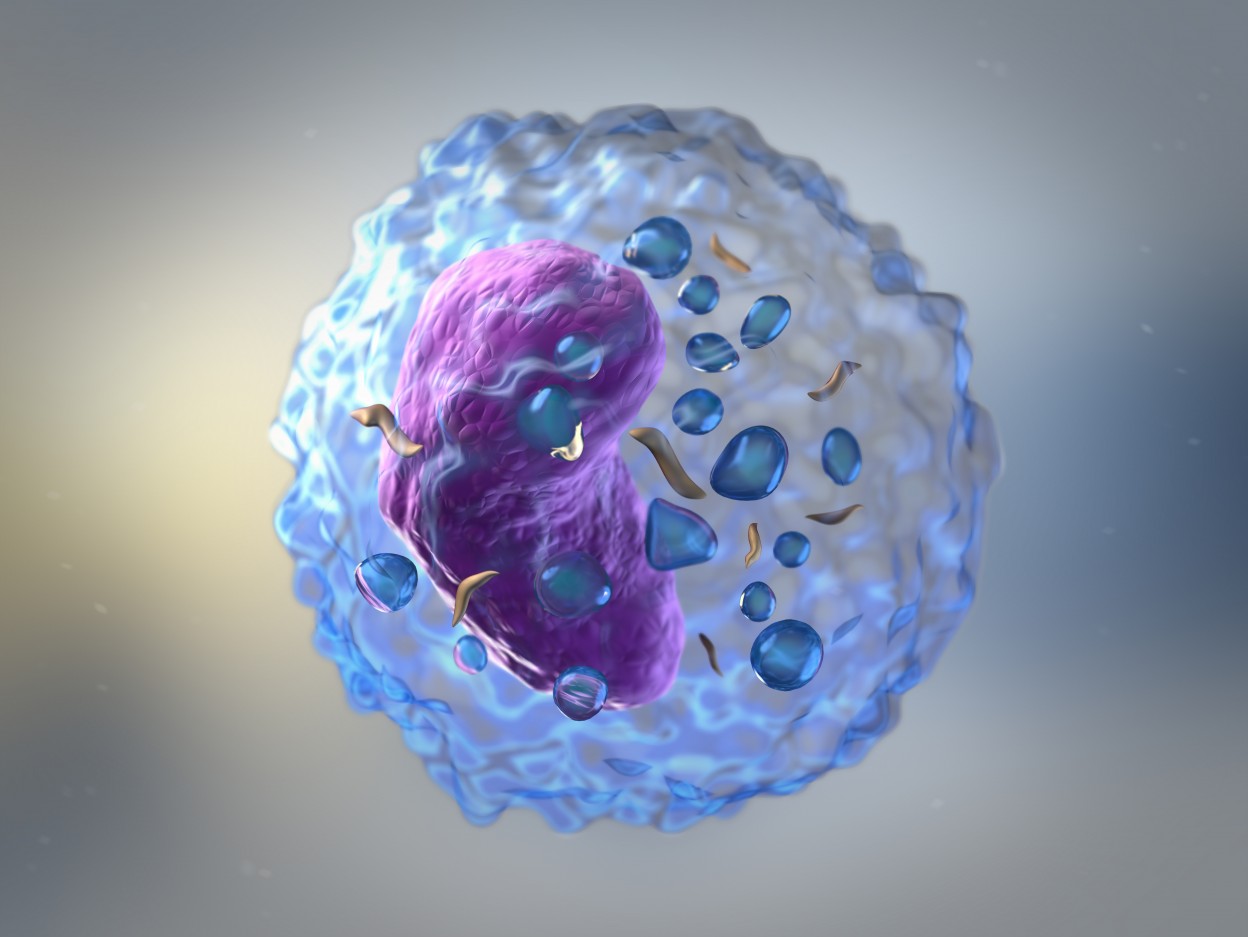

Exposure to a pathogen induces the selection of B-cells, a type of white blood cell, producing antibodies specifically against it. The process usually occurs in the lymph nodes and is controlled by two subtypes of another white blood cell type, T-cells.

T follicular helper cells help in the selection and activation of specific B-cells to fight the infection, whereas Tfr cells suppress B-cell activation and antibody production.

Under normal circumstances, these collaborative actions cause the production of antibodies that target specific foreign pathogens while limiting autoimmunity and excessive inflammation. However, abnormalities in these cells can lead to autoimmune disease.

When studying Tfr cells in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome, the research team found these patients have higher levels of Tfr cells in the blood compared to healthy people. This was the opposite of what researchers were expecting in a disease where there is an exacerbated production of auto-reactive antibodies.

These cells were also temporarily increased in the blood of healthy people when exposed to the flu vaccine, confirming the notion that Tfr cells are generated during immune responses involving antibody production.

The researchers also discovered that blood Tfr cells are not fully capable of suppressing antibody production because they are in an immature state. The regulatory activity of Tfr cells was found to be restricted to those present in tissues where antibody production takes place, like the lymph nodes.

This explains why increased numbers of blood Tfr cells is not an indicator of increased regulation of antibody production. Instead, it suggests that consistenly higher levels of Tfr cells in the blood indicate ongoing antibody-mediated immune responses, characteristic of autoimmune diseases.

The team is now investigating whether other autoimmune diseases also have increased blood Tfr cells, to evaluate their potential as biomarkers for those disorders.

In addition, researchers want to assess whether these cells can be used to identify those patients who may benefit from therapies that affect the production of auto-reactive antibodies.