Nerve Degeneration in Cerebellum Is Rare Manifestation of Sjogren’s Syndrome, Case Study Suggests

Written by |

Cerebellar atrophy — the deterioration of nerve cells in the cerebellum — is a rare but serious manifestation of primary Sjogren’s syndrome, according to a new case study from Iran.

The report, “Cerebellar degeneration in primary Sjogren syndrome,” was published in the journal BMJ Case Reports.

Sjogren’s syndrome is a chronic autoimmune inflammatory disease that has an estimated overall incidence of seven per 100,000 people. Sjogren’s syndrome can develop on its own as a primary condition, which is known as primary Sjogren’s syndrome, or in association with other rheumatic disorders, when it is called secondary Sjogren’s.

Both the peripheral nervous system (PNS) — the nervous system outside the brain and spinal cord — and the central nervous system (CNS) are known to be involved in the mechanisms that lead to primary Sjogren’s syndrome.

While PNS involvement is generally more common, many studies have reported that CNS manifestations happen in 2.5% to 60% of primary Sjogren’s patients, according to the case report.

Primary Sjogren’s syndrome patients commonly develop ataxia, which is a lack of voluntary coordination of muscle movements that includes gait abnormalities. But this is usually not associated with cerebellar atrophy, which takes place in the area of the brain responsible for muscle coordination and balance.

Physicians at Tehran University of Medical Sciences in Iran have reported the case of a primary Sjogren’s syndrome patient with both ataxia and cerebellar atrophy.

A 22-year old woman arrived at the hospital with gait disturbance 11 months before she was admitted. She had no familial history of gait problems or other neurological disorders. The patient had not been exposed to any toxins or drugs that could explain the symptoms.

She was unable to walk without assistance due to the presence of ataxia. She also had dysmetria (lack of coordination of movement), dysarthria (unclear speech articulation), and mild intention tremor (tremor that is present only during limb movement, such as reaching) in both legs and both arms.

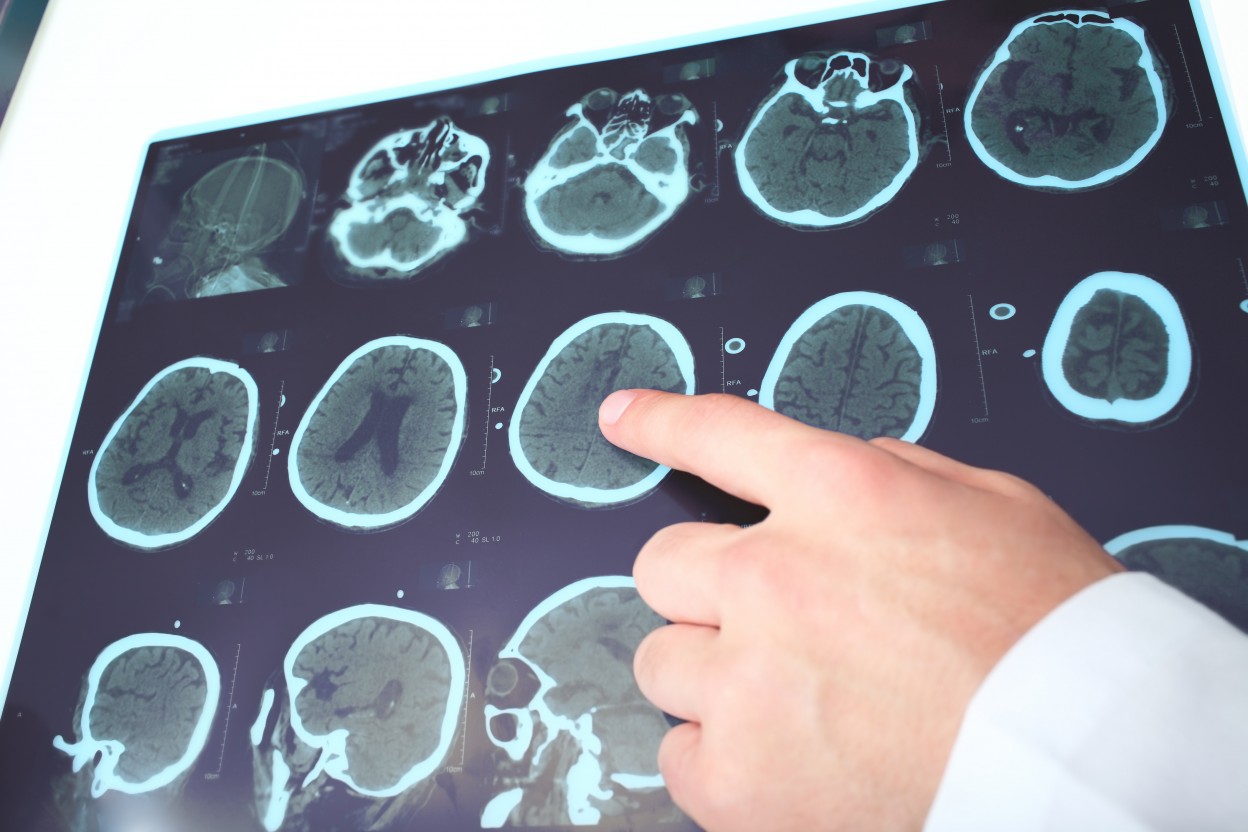

However, she did not demonstrate any cognitive impairment and her lab tests and a brain MRI came back normal. Therefore, she did not receive any treatment at the time.

The young woman was then admitted to the rheumatology clinic for treatment of joint pain and progressive gait disturbance. She had developed developed arthritis in both wrists and ankles nine months earlier, but had experienced a spontaneous recovery after several weeks using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

The patient did say that her gait worsened after that period. She also mentioned having dryness of both eyes and her mouth, which started five months before she went to the hospital.

The patient was then tested for Sjogren’s syndrome-related antigen A (anti-Ro-SSA) antibodies. The tests revealed she had significantly higher levels of anti-Ro-SSA compared to healthy individuals. She also tested positive for antinuclear antibodies and the rheumatoid factor, a hallmark of rheumatoid arthritis.

Physicians also conducted a biopsy of her salivary glands, which revealed infiltration of immune cells and chronic inflammation.

The patient’s brain MRI showed the presence of cerebellar atrophy, which puzzled physicians as cerebellar atrophy is very rare in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. So they tested her for other diseases, including alcohol abuse, drug abuse, nutritional deficiency, HIV infection, and celiac disease, all of which were negative.

Eventually, physicians diagnosed the patient with cerebellar degeneration related to primary Sjogren’s syndrome.

She was treated with with intravenous methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide. The medications led to significant improvement in the patient’s ataxia. In fact, her follow-up revealed that she could walk without assistance after eight weeks of treatment.

As a result, the investigators concluded that in rare cases, patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome can have manifestations of cerebellar atrophy.

“There is no consensus on a specific therapy for the management of [Sjogren’s syndrome] with CNS involvement,” the investigators wrote. “Hence, more studies are needed to identify the best treatment for cerebellar degeneration in primary Sjogren’s syndrome.”