Scientists Uncover Clues on How Autoimmune Diseases Develop, May Aid Diagnoses

The immune cells that produce self-targeting antibodies in cryoglobulinemia vasculitis (CV), a complication of Sjogren’s syndrome, are characterized by mutations that are known to drive lymphomas, a new study suggests.

This finding provides clues as to how autoimmune diseases develop, and could open new avenues for diagnosis and treatment, the researchers said.

The study, “Lymphoma Driver Mutations in the Pathogenic Evolution of an Iconic Human Autoantibody,” was published in the journal Cell.

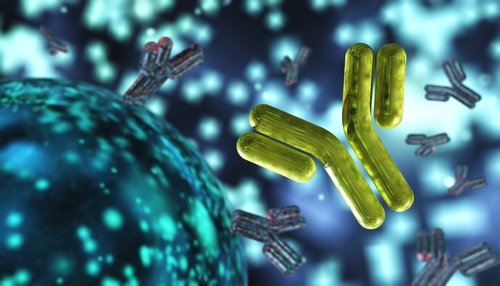

Antibodies are proteins produced by B-cells, a type of immune cells, to fight off infections. These proteins can bind to their targets, typically bacteria and viruses, with high specificity. Sometimes, however, self-targeting antibodies — called autoantibodies — are produced, which can lead to a variety of autoimmune diseases.

In an autoimmune disease, the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own healthy cells.

Exactly how autoantibody-producing B-cells develop has been something of a mystery. Indeed, there are several “quality control” steps in B-cell development that should preclude autoantibody production. If those steps are working properly, the B-cells that make autoantibodies should be destroyed.

Part of the problem in studying the development of these “rogue” B-cells has been that they are comparatively rare in the bloodstream. But modern technologies, such as single-cell sequencing, now allow for the identification of these individual cells.

In the new study, researchers at the Garvan Institute of Medical Research, in Australia, used these technologies to identify rogue B-cells in four people with CV that had developed as a complication of Sjogren’s syndrome.

CV was chosen because it is characterized by a very specific type of autoantibody, called a rheumatoid factor. This antibody binds to (self) proteins in the blood. Under certain temperature conditions, it forms clumps that cause damage to blood vessels and organs.

About 80% of people with Sjogren’s have these antibodies at detectable levels, usually without symptoms. But in 30% of cases, these antibodies end up causing CV.

The researchers performed global analyses of cells at multiple levels, including protein, DNA, and RNA — molecules that provide information as to what genes are active and to what extent. This allowed them to identify cells that were making rheumatoid factor, and to determine which mutations these cells had.

First, the researchers noted that rogue B-cells had mutations in antibody-coding genes. To some degree, this is expected — somatic mutations, or alterations in DNA, in these genes is part of what allows antibodies to achieve their specificity.

What was especially striking was that, in molecular experiments, autoantibodies with these mutations formed clumps characteristic of CV. Removing these mutations also removed the disease-causing clumping ability – essentially, turning the disease-causing autoantibody into its benign predecessor.

In addition, the rogue B-cells had mutations that are known to drive lymphomas — cancers of immune cells, such as B-cells. These mutations drive the growth of these B-cells, prompting their activation and, therefore, antibody production. Additionally, some of these mutations promote the development of additional mutations, including those in the antibody-coding genes.

Detailed analyses of all of these mutations allowed the researchers to sort out the order in which they occurred. They determined that the pathogenic, or disease-causing mutations in antibody-coding genes came to be after the lymphoma driver mutations.

This suggests a step-by-step process for the development of rogue B-cells. First, B-cells go through development as usual. Some of these cells have antibody genes that are close to the kind that would cause CV, but they don’t have all the necessary features to be disease-causing. Then, these cells acquire lymphoma driver mutations, which prompts their rapid growth and the acquisition of new mutations. Finally, the right antibody-coding mutations are acquired to enable the production of disease-causing rheumatoid factor.

“Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis is correlated with an ~2-fold higher risk of B-cell lymphoma in people with [Sjogren’s syndrome],” the researchers said.

“Here we provide a mechanistic explanation for that correlation in a direct causal sequence starting with lymphoma driver mutation followed by random … mutations, a subset of which convert a benign autoantibody into a pathogenic one,” they said.

According to the researchers, these findings could open new avenues for early diagnosis or treatment of autoimmune diseases.

“If we can diagnose a patient at these stages, it may be possible to combine our knowledge of these mutations with new targeted treatments for lymphoma to intervene in disease progression or to track how well a patient is responding to treatments,” Joanne H. Reed, PhD, a co-author of the study, said in a press release.