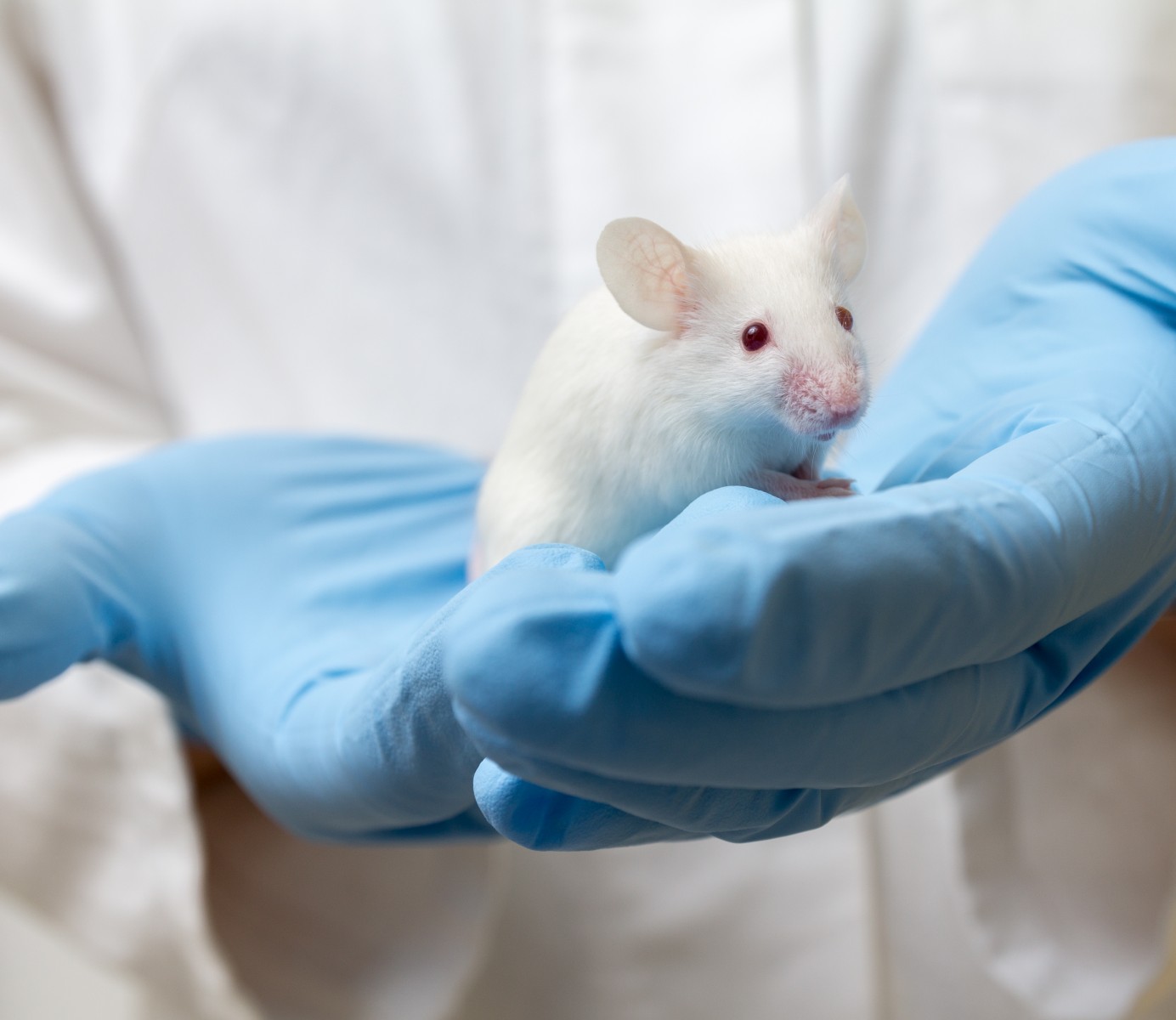

Mouse Study Suggests Benefits of Diabetes Drug in Sjögren’s Syndrome

A new study in mice suggests that metformin — a drug typically used to control blood sugar levels in diabetes — may be able to reduce inflammation and damage to the salivary glands in Sjögren’s syndrome.

The study, “Metformin improves salivary gland inflammation and hypofunction in murine Sjögren’s syndrome,” was published in the journal Arthritis Research & Therapy.

Metformin has several known effects on the body; it is best known for reducing blood glucose in the treatment of diabetes. Metformin also has anti-inflammatory effects.

This led researchers in this study to hypothesize that metformin might have therapeutic benefits in Sjögren’s syndrome, which is defined by inflammation.

To test this hypothesis, the researchers used a mouse model of non-obesity-induced diabetes. These mice develop Sjögren’s syndrome-like symptoms as a secondary effect of the diabetes, which makes them a useful study model.

Mice were given either metformin or a placebo in their drinking water, and the researchers tracked the mice’s salivary function and the status of their immune systems.

In untreated mice, salivary production gradually decreased over the course of the study period. However, mice given metformin showed no such decline; their saliva production was significantly higher than that of untreated mice after a few weeks.

The metformin-treated mice also showed many signs of reduced inflammation in their salivary glands. There were fewer inflammatory cells present, as well as lower levels of inflammatory signal molecules.

Additionally, when the researchers analyzed the specific types of immune cells present in both groups of mice, they found that metformin-treated mice had more anti-inflammatory cells — such as regulatory T cells, called Tregs — relative to the number of pro-inflammatory cells, specifically Th1 and Th17 cells, both T cells that secrete molecules that drive inflammation.

Additionally, B cells, which make antibodies, were less likely to be active in metformin-treated mice, as evidenced both by cell-level changes and lower systemic levels of antibodies in the mice.

The data support the researchers’ hypothesis. They concluded in their paper that “metformin reduced salivary gland inflammation and restored the salivary flow rate in an animal model of [Sjögren’s syndrome].”

It should be pointed out that, because metformin is traditionally a diabetes drug, it is conceivable that effects seen for the secondary disease (Sjögren’s syndrome) might instead be due to effects on the primary disease (diabetes).

The researchers noted that they did not include mice who became hyperglycemic (high blood sugar, indicative of diabetes) in their analysis in order to focus on the secondary symptoms. Still, this is an acknowledged weakness of the study, and the researchers wrote that further studies in a primary model of Sjögren’s syndrome would be “required” to validate these results.