Gut Microbiota May Be Key to Sjögren’s Symptoms and Offer Way to Treating Them, Study Says

Written by |

Healthy gut microbial communities — its microbiota — can ease Sjögren’s syndrome-associated symptoms and immune responses, according to a study in a mouse model of the disease.

These results show a protective role of the gut’s microbiota, and one could serve to develop new therapies for Sjögren’s patients.

The study, “Protective role of commensal bacteria in Sjögren Syndrome,” was published in the Journal of Autoimmunity.

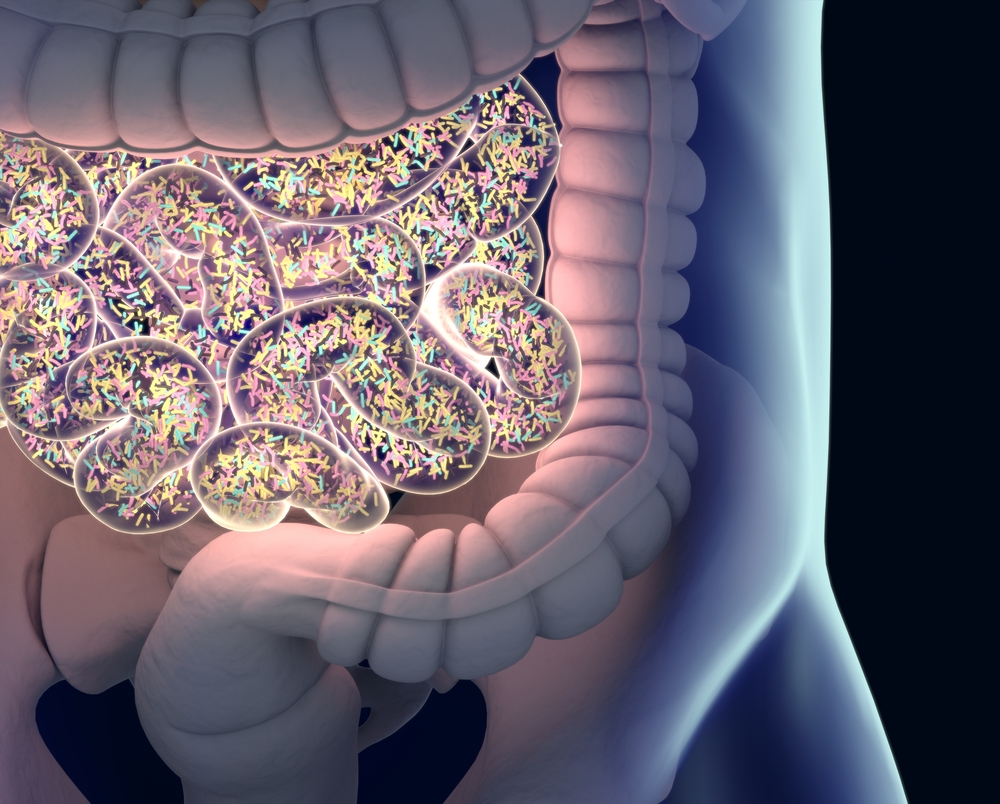

The gastrointestinal tract is colonized by the intestinal microbiota, a vast community of commensal (“friendly”) bacteria, which plays an important role in gut health. These bacteria help to maintain a balanced gut function, protect against disease-causing organisms (pathogenic organisms), and influence the host’s immune system.

A healthy balance of the gut microbiota depends on environmental factors such as diet, exposure to micro-organisms, and antibiotic therapy, and an imbalance can trigger gut dysfunction, allergies, obesity, and inflammatory diseases.

Recently, patients with Sjögren’s syndrome were found to have an imbalance in their gut microbiota, with a lesser abundance of “friendly” bacteria and higher numbers of pathogenic organisms.

Sjögren’s syndrome is an autoimmune disease characterized by the infiltration of immune cells into secretory glands — primarily the lacrimal and salivary glands. These cells incorrectly recognize the glands’ tissue as foreign and fight it, leading to cell death and reduced production of tears and saliva, resulting in dry eyes and dry mouth.

Researchers evaluated the role of gut microbiota in the lacrimal gland and eye function in a mouse model of Sjögren’s syndrome.

Mice grown in a germ-free environment — meaning that they do not have gut microbiota — showed worse dry eye disease and eye dysfunction, with accelerated accumulation of autoreactive IFN-γ-producing immune cells and glandular destruction, compared to mice grown in a normal environment.

IFN-γ, a communication molecule associated with several immune responses, has been shown to be involved in the development of autoimmune diseases.

In mice with healthy gut microbiota, the induction of a strong microbiota imbalance — done by administering a cocktail of oral antibiotics — also worsened eye dryness and promoted the production of these autoreactive immune cells.

When researchers transferred immune cells from germ-free mice to mice that lacked an immune system, they observed a more severe Sjögren’s-like disease than was seen in mice given cells from normal-environment animals.

These findings suggest an association between gut microbiota and autoimmune responses, and that healthy gut microbiota or their products have immunoregulatory properties that delay autoimmunity and Sjögren’s-like symptoms.

The reconstitution of the gut microbiota in germ-free mice reversed the spontaneous dry eye disease, and lowered the generation of autoreactive immune cells, suggesting “that manipulation of the gut microbiota has the potential to be a novel therapy for Sjögren’s syndrome,” the researchers wrote.