Bacterial Molecule Can Slow Sjögren’s Progression, Preclinical Study Suggests

Written by |

Oral treatment with a molecule produced by bacteria, called colonization factor antigen I, can reduce or halt the progression of Sjögren’s syndrome, a mouse study suggests.

Researchers believe these findings provide the basis for future testing in patients with Sjögren’s.

The study, “Stimulation of regulatory T cells with Lactococcus lactis expressing enterotoxigenic E. coli colonization factor antigen 1 retains salivary flow in a genetic model of Sjögren’s syndrome,” was published in the journal Arthritis Research & Therapy.

Sjögren’s syndrome is an autoimmune disease resulting from the immune attack on glands in the eyes and mouth that reduce salivary and tear flow. While there is no vaccine or available treatment, patients rely on therapies such as artificial saliva and eye lubricants to alleviate disease symptoms.

Oral treatment with a bacterial protein known as colonization factor antigen I (CFA/I) fimbriae, from Escherichia coli bacteria, has been shown to protect against several autoimmune diseases, including arthritis and type 1 diabetes.

Another bacteria, called Lactococcus lactis, was recently adapted to express CFA/I fimbriae. These bacteria were shown to effectively suppress inflammation by the induction of regulatory T-cells (Tregs) — which are negative regulators of the immune system, meaning they work to shut down excessive inflammatory responses.

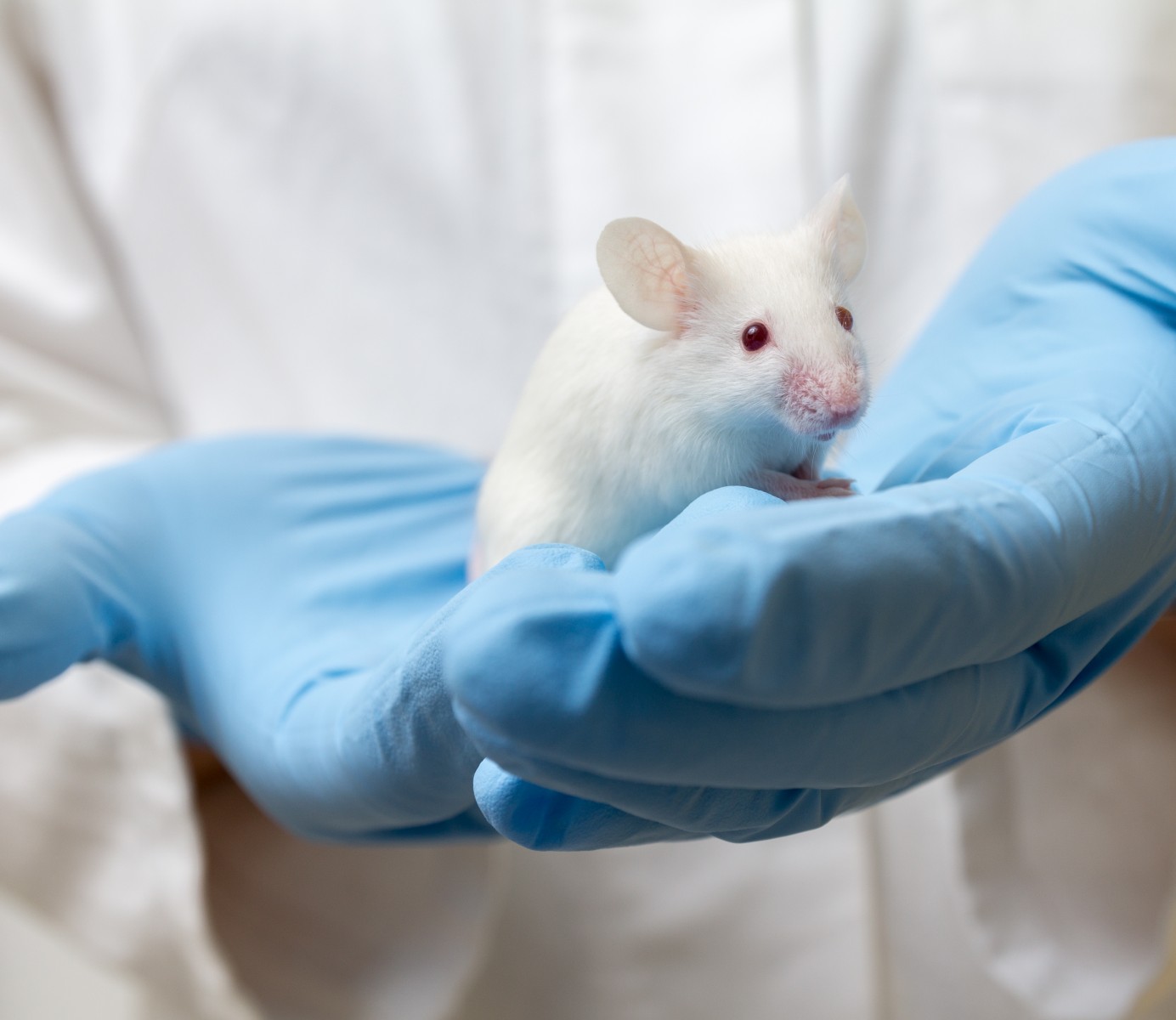

Now, a team led by researchers at the University of Florida used a mouse model of Sjögren’s syndrome (NOD mouse model) to assess if oral treatment with Lactococcus lactis CFA/I fimbriae (LL-CFA/I) was able to maintain salivary flow in mice.

The team treated six-week-old NOD mice with LL-CFA/I every three weeks, and compared the results with those of mice receiving only Lactococcus lactis (without CFA/I fimbriae) or a control solution (control groups).

Three doses of LL-CFA/I were tested: a low dose of 50 million colony-forming units (CFU, the number of viable bacteria), a medium dose of 500 million CFUs, and a high dose of 5,000 million CFUs.

Results showed that mice treated with LL-CFA/I maintained their salivary flow up to 28 weeks of age and had significantly reduced inflammation in saliva and tear glands when compared to control mice, which showed a progressive reduction in their salivary flow rate.

Interestingly, NOD mice treated with the high dose of LL-CFA/I failed to maintain their salivary flow when compared to mice given lower doses.

“Hence, CFA/I fimbriae conferred protection against SFR [salivary flow rate] loss, and the protection is dose-dependent,” the researchers wrote.

Additionally, mice treated with low-dose LL-CFA/I had a significant increase in the production of Tregs and a significant reduction in the expression of multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines — small proteins secreted by cells that mediate and regulate immune and inflammatory responses.

“Collectively, these data showed that dosing with [50 million] CFUs of LL-CFA/I every 3 wks provides SFR maintenance,” the team wrote.

A specific type of immune cell, called CD4+T-cells, plays a major role in immune responses. The researchers found that the transfer of CD4+ T-cells from LL-CFA/I-treated mice to control NOD mice restored their salivary flow, suggesting that these cells are key players that “confer protection against further progression of [Sjögren’s] symptoms,” the researchers wrote.

Overall, the “data demonstrate that oral LL-CFA/I reduce or halts [Sjögren’s] progression, and these studies will provide the basis for future testing in [Sjögren’s] patients,” the team concluded.